I 9-9-6’d my life for this?

We glorify startups as a society. The sayings have crossed the chasm from business mantras to motivational quotes - move fast and break things; fail often so you can succeed sooner; if you build it, they will come; do what you love.

And while there is some merit to these tomes, how many times have we seen someone build yet another sales ops support product, another low-code design engine, or another marketing automation app, another enterprise productivity tool engineered to make [x] non-technical manager’s life ‘easier’ and asked silently – is this really the biggest problem you saw that needed fixing?

Heart-led, technically strong founders with a strong pull to innovate exist – yet the vast majority are not focused on building solutions to our society's most vexing problems.

When people think of startups, they think of innovation, ingenuity, scrappiness, creativity, and intelligence. In fact, these descriptors are so compelling that 25% of Harvard Business School Graduates are founders or early-stage joiners at graduation. At Massachusetts Institute of Technology - America's flagship technological research institute - nearly 20% of its students go straight to startups.

With all this incredible talent and brainpower, what problems are these people putting their hearts and minds behind?

Meanwhile, categories like developer tools, infrastructure, and generic B2B software dominate YC’s recent batches and its directory, with external write‑ups of the S25 class highlighting ‘100+ AI startups’ and a sea of productivity and enterprise tools. When you stack that against the tiny slices for healthcare delivery, childcare, eldercare, housing, and skills, it’s not an exaggeration to say that most of the hustle — the sleepless nights and breathless pitch decks — has gone into making enterprise software marginally less annoying.

There is a mismatch between what is being built and what Americans hope will come to pass in their lifetimes. Gallup finds that 70% of Americans express confidence in small business—higher than the military, the church, and every branch of government. The faith is there. Americans believe that the "Little Guy" can solve what the government cannot.

But look at the pipeline. We aren't incubating the companies to fix our most vexing problems. We are incubating companies to fix the problems that previous generations of startups created for their businesses.

And it’s not like the problems are hard to find. The people suffering from them aren’t hidden. In fact, sometimes it just takes opening your phone, and the problem will reveal itself to you - with a photo and an undeniable series of hard data.

I was doomscrolling on Instagram on one of my favorite meme accounts that pokes fun at Millennials and our awkward rise to adulthood—the too-thin eyebrows, the era of the boy-band, the "going out tops" we all wore. Emo. But then a photo of a check stopped me cold. At first I thought they had been hacked. But when I saw it was dated January 27, 1997 and written to Kiddie Academy, a childcare chain, for one week of tuition, I was intrigued.

The amount was $85.00.

The caption was a fun "what a trip" shoutout to moms who keep old receipts. But I opened the comments, and poof! The nostalgia vanished. It was replaced by a wall of absolute desperation.

Adjusted for inflation, that $85 should be about $180 today. But parents in the comments aren't paying $180. They are paying $400, $550, even $635 a week for the exact same service. One mother wrote that she pays $32,400 a year for twins while earning $40,000 from a full-time job, leaving a net profit of $7,600.

You might assume that money is going to the caregivers, but the comments revealed the opposite. Childcare providers chimed in, saying that while tuition has quintupled, their wages haven't. Veteran daycare staff with 27 years of experience reported they are still earning near minimum wage, often $12 to $15 an hour.

This is a structural break. Parents are going broke paying for care, and providers are staying broke delivering it. As one parent in the thread put it: "I literally just work to barely live and get by. It’s like a never-ending hamster wheel".

These people don't want an AI agent to make it faster to pull a query from Excel. What they want is a way to earn a paycheck without the entire paycheck going to their kid’s childcare.

The economy needs people from all walks of life to participate. Men, women. Old, young. Black, brown, yellow, white, pink. And the beauty of America is we are free to pursue the careers or employment of our choosing - that's the American dream. But what happens when the mix of people becomes clustered in individual-focused endeavors that lose sight of the parts of a whole that make a functioning society? Do individuals contribute to or take away from the availability of the American dream?

The question isn't whether smart, mission-driven founders exist. They do. The question is why they're not here — building in the markets that actually shape whether the American Dream stays reachable. That Instagram comment section was a market screaming for a solution. Parents broke, providers broke, everyone stuck. So, where are the founders who could actually build something?

There are 33 million entrepreneurs in the United States. Not corporate employees climbing ladders. Not product managers angling for their next PM job. Entrepreneurs — people who've already made the leap, already chosen to build something rather than manage something.

Five million new business applications hit the IRS every year. That's the pipeline.

They're all heart-led. The question is where they point it.

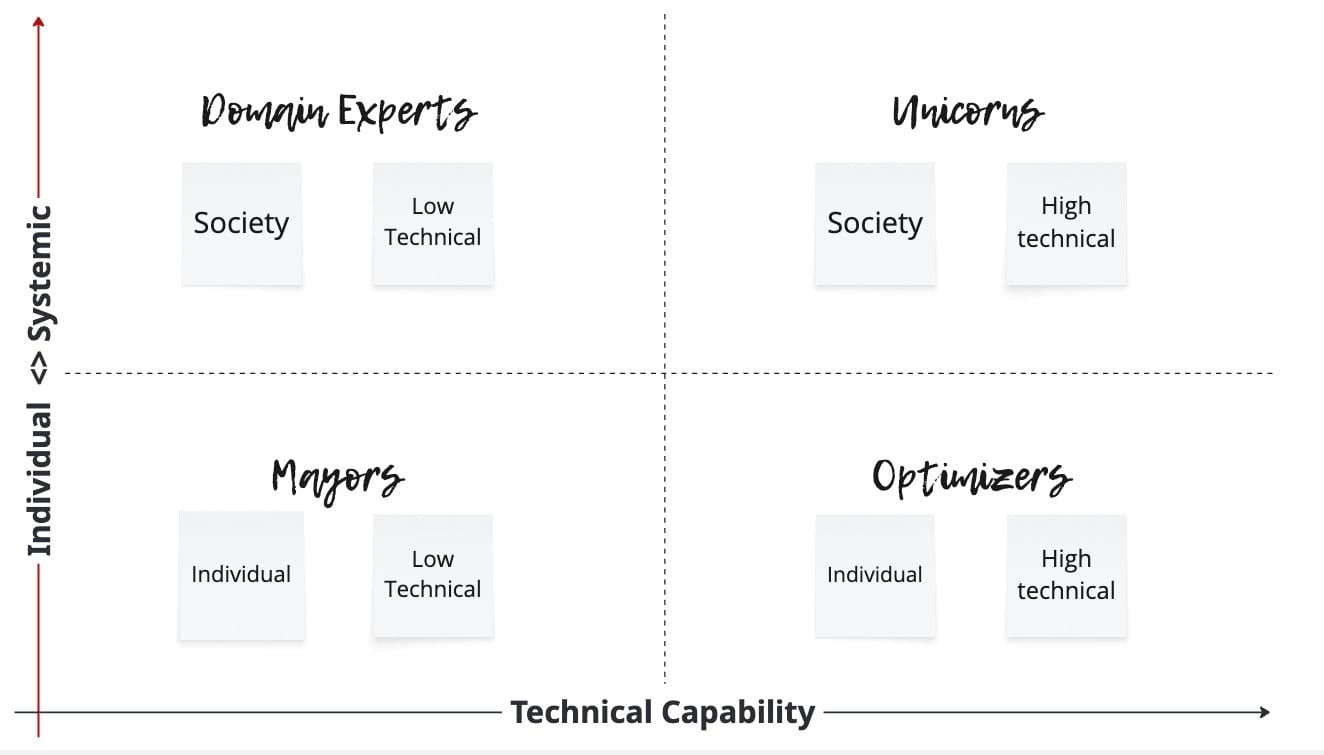

The vertical axis is focus: individual or systemic. The horizontal is technical capability — specifically, the ability to build software products from scratch that leverage data and AI to create efficiencies. Not domain expertise. Not research chops. The Mark Cuban type, not the Jamie Dimon type.

Mayors build local empires. The nutritionist with great content and a thriving practice. The franchise founder scaling through locations, not code. They help real people. They can get rich. They're not trying to change how markets work.

Optimizers have the technical firepower but point it at individual returns. They build products users love in markets where the playbook works. Dev tools, fintech, B2B SaaS. Rational choice, clear incentives.

Domain Experts see the systemic problem — they've lived inside it. Clinicians, researchers, policy people. They have the conviction but not the software DNA. Put them inside a Medtronic and they thrive. Ask them to build from zero and they stall.

Unicorns have both. Systemic focus and the technical ability to build from nothing.

That quadrant isn't empty by any means. Founders in it are building Anthropic. Sail Drone. Climate tech. Energy infrastructure. They're pointed at systemic problems — just not the ones that determine whether ordinary Americans can make informed choices about their healthcare, access childcare or care for their aging loved ones, or build a sustainable career.

One bright spot: housing. Culdesac raised $30 million from Khosla and Founders Fund to build car-free neighborhoods — people are living there now. Joe Gebbia left Airbnb and raised $41 million to help Samara build backyard ADUs. Zippy raised $26 million to make manufactured home loans actually work. The physics allow it. Something will pan out.

Look at housing, and you see Unicorns taking shots. Look at healthcare, and you see a graveyard of billion-dollar valuations.

But why is the picture so much more bleak in these other areas? Healthcare delivery. Childcare. Eldercare. Skills training. Where are the equivalents?

The pipeline is a trickle. Look at Y Combinator's Summer 2025 class: 80-85% B2B or enterprise-focused, 30% developer tools, healthcare at 10%, and falling. Education and government tech at 1% each. Go to A16Z's portfolio, Sequoia's, and Founders Fund's — count the healthcare companies. Now subtract biopharma. Subtract the admin-tech plays optimizing billing and prior authorization. What's left?

Of the venture capital that does flow to healthcare, the vast majority goes to biopharma — a 1:1 game where a single drug might save a narrow patient population after a decade of development and a billion dollars in clinical trials. What's left often props up the administrative infrastructure that makes the system dysfunctional in the first place: billing optimization, prior authorization automation, claims processing. Not companies that fix the system. Companies that help the system extract more efficiently. Meanwhile, 30% of every healthcare dollar goes to administrative overhead that exists to optimize reimbursement, not care. The complexity isn't a bug — it's a business model.

Mark Cuban looked at drug pricing and said publicly what everyone in the industry already knew: the system is designed to extract, not heal. Cost Plus Drugs is his answer — margin transparency, cutting out the PBM middlemen, refusing to play the game. But Cuban has something most founders don't: the capital, the profile, and the FU money to build around the system without asking permission. The question is whether there's a path for founders who don't have $4 billion in liquidity to burn.

And the founders who do get through with the right focus? They still fail — because the playbooks don't work here.

It's not that people aren't trying. Thousands of primary care doctors have fled to concierge medicine — but if you can't pay $200 a month, you don't get it. Retail and primary‑care plays like Walmart Health, Walgreens’ VillageMD, and Forward raised billions collectively, then faced clinic closures, multi‑billion‑dollar write‑downs, or outright shutdowns when the unit economics didn’t work. Forward burned through $650 million and shut down overnight last November. Carbon Health laid off 500 people and closed clinics across the country.

The pattern is the same every time: you can survive the startup phase, but you can't afford to scale. A friend who runs marketing for a biomedical surgical company put it bluntly — they can be a startup while they navigate testing and approval, but to implement at scale, the only exit is to sell. The costs are too high.

That's not a shortage of heart. That's not a shortage of capability. That's a market where the physics don't allow independent companies to survive.

Look at housing and you see Unicorns taking shots. Look at healthcare and you see a graveyard of billion-dollar valuations.

Three reasons:

First, these markets are hairy. Regulated, slow, unglamorous. In the case of healthcare, care delivery and care are conflated - the expertise amassed from years of caring for patients and researching biologics in labs cannot be hacked. But that same expertise isn’t needed to understand how to give patients greater agency in their health choices. To inform them of their rights and roles and responsibilities. To reduce the reliance on the wasteful administrative state. The physics are different and smart founders sense it before they can articulate it.

Second, they're dismissed. Childcare is a "women's problem." Healthcare is someone else's job to fix. Eldercare is a ‘cultural thing’ and pushed off like the discussion of death to the absolute last minute. The founders who end up here usually got here through personal crisis — they watched a parent navigate the system, or they couldn't find childcare themselves. We have a culture of immortality until it happens to us.

Third, the playbooks from other industries fail. You cannot move fast and break things in a market where the government is your co-pilot. You cannot software your way out of caregiver-to-child ratios. You cannot move fast and break things in a market where the government is your co-pilot. You cannot software your way out of caregiver-to-child ratios. You cannot growth hack through an MRI billing system designed to resist transparency. You can't market to a customer who doesn't believe it's their responsibility to understand the cost of their care and comparison shop based on price. And you can't scale your way out of the 53 million Americans providing unpaid care for aging parents — not because they chose it, but because there's no alternative they can afford. That's $600 billion in uncompensated labor, invisible to GDP, grinding down the people who can least afford to give.

That's the filter. Not a lack of heart. Not a lack of capability. A rational read of the physics — and a market that doesn't reward what these founders are good at.

The Autopsy

The 2x2 doesn't show an empty quadrant. It shows an underpopulated one.

The top right — technical firepower plus regulatory fluency — has real companies and real founders. But it's sparse. Some people don't see the opportunity; they assume broken markets are unprofitable by definition. Others assume insiders have it locked — that you need to be a former CMS administrator or hospital CFO to play. And some try, hit the physics constraints, and pivot before they find a model that works.

Here's what that looks like up close.

The Move Fast Trap

Papa raised $240 million and hit a $1.4 billion valuation by 2023. The pitch: a TaskRabbit for seniors — gig workers called "Papa Pals" who'd help older adults with errands, transportation, and companionship. Medicare Advantage and Medicaid plans signed on. SoftBank led the Series D. The mission was real.

Then Bloomberg reviewed 1,200+ confidential complaint reports. Dozens of allegations of sexual harassment and assault — of both seniors and caregivers. One pal was hired despite prior felony drug convictions and a misdemeanor domestic assault charge; he was later charged with raping a 70-year-old client. The company had shared direct phone numbers between clients and pals instead of anonymizing them — standard industry practice they'd skipped for speed.

The Glassdoor reviews tell the same story. Workers describe policy changes without notice, bot-only communication, background checks that cleared people for weeks before flagging disqualifying offenses. One pal was asked to clean human feces off carpet for $17/hour while the company scaled toward unicorn status.

Senator Bob Casey opened an investigation. CMS started reviewing complaints. Humana, Aetna, and Molina declined to renew contracts.

Papa applied a gig economy playbook to a population that can't absorb platform risk. When trust is the product and your customers are vulnerable, "move fast and break things" doesn't disrupt the system — it breaks the people you were supposed to serve.

They understood the problem. They had the capital. They didn't have the operating system.

Baumol's Trap

You'd think childcare availability and affordability is something everyone supports. Not true.

Set aside the social engineering debates — the far right who want women to stay home, the far left who want all childcare subsidized and state-owned. The groups who employ low-wage workers or represent independent businesses were often the most resistant to anything that would require them to provide or accommodate care. The common refrain: it would bankrupt their members or lead to fewer jobs. Not inaccurate — but they didn't come with solutions. Most didn't return my calls at all.

In 2016, I was advising Congressional leadership on childcare policy. The think tanks were thoughtful — AEI economists like Michael Strain could point me to reams of data, studies, surveys, workplace trends. Care.com briefed me multiple times. SHRM engaged seriously. But solutions were scarce. Everyone understood the problem. No one had a model that worked.

A caregiver can only safely watch four toddlers. That's not a feature to optimize; it's physics. You can't software your way out of Baumol's cost disease. The founders who understand this avoid the sector entirely. The ones who don't raise money, hit the wall, and pivot to B2B — selling software to childcare centers instead of serving families directly.

But childcare is also where you can see the model that actually works.

In 2001, Congress created Section 45F — a tax credit for employers who provide childcare to their employees. Legal validated it. Finance could model it. Almost nobody used it. By 2016, fewer than 300 corporate tax returns claimed it out of 70,000+ eligible filers.

The policy existed. The problem was everything else.

In 2017, Ivanka Trump started meeting with lawmakers on both sides of the aisle. She diagnosed the structural problem clearly: "You have care providers who are working at below poverty wages, you have parents who can't afford the care, and you don't have a robust ecosystem of facilities because it's a low-margin business with high liability. It's just a fundamentally flawed system."

She was right. But diagnosis isn't delivery.

What was missing wasn't policy or market innovation — it was the bridge between them. That bridge started showing up in the 2020s. Brokers like TOOTRiS emerged, turning "build a childcare center" into "pick from a catalog." They handle provider matching, eligibility tracking, payment processing. The employer doesn't have to understand childcare licensing — they pick a plan and their finance team models the tax credit. What felt like a capital project became a benefits decision.

Then, in July 2025, the One Big Beautiful Bill tripled the credit — from 25% to 40% (50% for small businesses) — and capped it from $150K to $500K ($600K for small businesses). Senator Shelley Moore Capito championed the provisions. Critically, it let small businesses pool resources and claim the credit through third-party providers.

The scaffolding is now complete. And employers are moving.

In August 2025, Toyota announced four new childcare centers at manufacturing plants in North Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, and West Virginia — capacity for over 1,000 children across two shifts, aligned with plant production schedules. This builds on 24-hour facilities they've operated in Kentucky since 1993. "Offering childcare motivates and empowers our team members, makes our industry more inclusive, and helps our smallest learners of today become our biggest leaders of tomorrow," said Denita Neville, VP of Corporate Shared Services.

Manufacturing gets it. The ROI is documented. The infrastructure is administrable. Policy supports it without penalizing workers who don't have children.

This is what the model looks like: policy creates scaffolding, private market builds connective tissue, employers prove ROI, and a coordination problem becomes solvable. Not government-led. Not VC-funded disruption. The third path — where the people who understand both systems build the bridge between them.

Here's the math: roughly 20,000 large employers in the U.S. employ about 60 million people. If 25% of them offered childcare benefits — 5,000 companies covering 15 million workers — you'd see a measurable shift in workforce participation among parents with young children. That's not a policy fantasy. That's a coordination problem with a known solution.

The question isn't whether it works. It's why only 12% of workers have access to childcare benefits, 6% among part‑time/lowest‑income workers, despite decades of evidence.

The Admin Wedge

I needed an MRI. Same procedure, same city, eight providers. The quotes ranged from $342 to $1,900 — a 5.5x variance for identical imaging.

St. David's, my doctor's system, quoted $1,400 but couldn't tell me if that was my insurance copay or self-pay. ARA wanted me to sign a contract agreeing to pay $1,900 if insurance fell through — before they'd even schedule me. One facility claimed to be in-network; my insurance said they weren't. Another never responded about insurance at all.

I had been bleeding for five months. And instead of getting care, I was project-managing a procurement process — calling billing departments, comparing quotes, waiting for prior authorization, navigating the gap between what insurance said and what providers said.

This is what it means to be a "healthcare consumer." You're supposed to shop. But the prices aren't posted. The providers don't know their own rates. The insurance company and the facility disagree about whether they're in-network. And you're doing all of this while you're sick.

Startups see this and think: "I'll build a price transparency tool." But transparency doesn't solve the problem. The problem isn't that patients don't know the prices — it's that the prices are artifacts of negotiated rates, facility fees, chargemaster games, and deliberate opacity that have nothing to do with the cost of delivering care.

The wedges that work aren't the ones you'd expect. Radiology Assist built a nationwide network of over 1,000 imaging centers, brokering excess MRI capacity for self-pay patients — arbitrage, not transparency. Longhorn Imaging grew to eight locations in Austin by building around personal injury attorneys who need fast imaging for discovery — a completely different customer with completely different incentives than patients shopping for care.

You can't growth-hack through an admin wedge by making the existing system more legible. The complexity is the product. The companies finding traction aren't making healthcare easier to navigate. They're building around customers who don't have to navigate it at all.

The founders who populate the top-right quadrant don't just have better tech or bigger hearts. They have a different operating system.

The most common mistake I see is a founder hitting a regulatory wall and trying to hire their way out of it.

"Let's slot in a Head of Policy." "Let's slot in a Marketing Lead."

This fails because in broken markets, government is a co-pilot — not a compliance checkbox. You cannot delegate the physics of the market to a functional hire. A Head of Policy can't fix your unit economics. A Marketing Lead can't message their way around Baumol's trap. The Admin Wedge doesn't care about your brand positioning.

These aren't just failure modes. They're the physics of markets where your competitors aren't other startups. Your competitors are resignation and mortality. Kids age out of childcare. Aging parents die. Patients either recover or they don't. The market doesn't reward patience — it just runs out the timer.

The childcare story isn't about policy winning or employers being generous. It's about what happens when someone finally connects the scaffolding to the business model — when the tax credit stops being a line-item legal mention and becomes the load-bearing wall of your workforce strategy. That took 24 years. It took brokers building connective tissue. It took Toyota to decide this was operations, not benefits.

The work isn't glamorous. It means staring directly at the structural constraints — the physics of caregiver ratios, the actuarial reality of insurance markets, the administrative overhead that eats margin before you ever touch a patient or a parent — and designing a business model that survives them.

But if you're willing to do that work, you have almost no competition. The founders with technical skills avoid these markets. The founders with the heart burn out or get captured. The slot is wide open for someone who can hold both.

There's a phrase that floats around consciousness circles — burnt-out founders and executives looking for work that matters: "pure but poor." Brian Whetten talks about this in his second mountain work — the trap of believing that meaningful work requires sacrifice, that you can't build something sustainable while also building something good. It's the same pattern that catches people trying to live monastically, so committed to spiritual purity that they can't integrate into the real work of society.

The opportunity isn't to be righteous and broke. It's to look up from the valley and see that broken markets are the second mountain — the place where technical skill, hard-won pattern recognition, and genuine care for people can compound into something that lasts. The founders who've been stuck in "pure but poor" already have the heart. What they need is an operating system that doesn't require them to choose between impact and sustainability.